This article explains everything you need to know about the premium tax credits (premium subsidies) created by the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare) and enhanced by the American Rescue Plan and Inflation Reduction Act. These subsidies are available through the exchange/Marketplace in every state.

Open enrollment for marketplace plans runs from November 1 to January 15 in most states. (This schedule also applies to plans purchased outside the marketplace, but subsidies are not available outside the marketplace.) Outside of open enrollment, enrollment is possible if a person qualifies for a special enrollment period, most of which are triggered by a qualifying life event.

The American Rescue Plan (ARP), which provides significant, albeit temporary, enhancements to the ACA, was signed into law by President Biden in March 2021. And the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which Biden signed into law in August 2022, extends some of these enhancements through 2025.

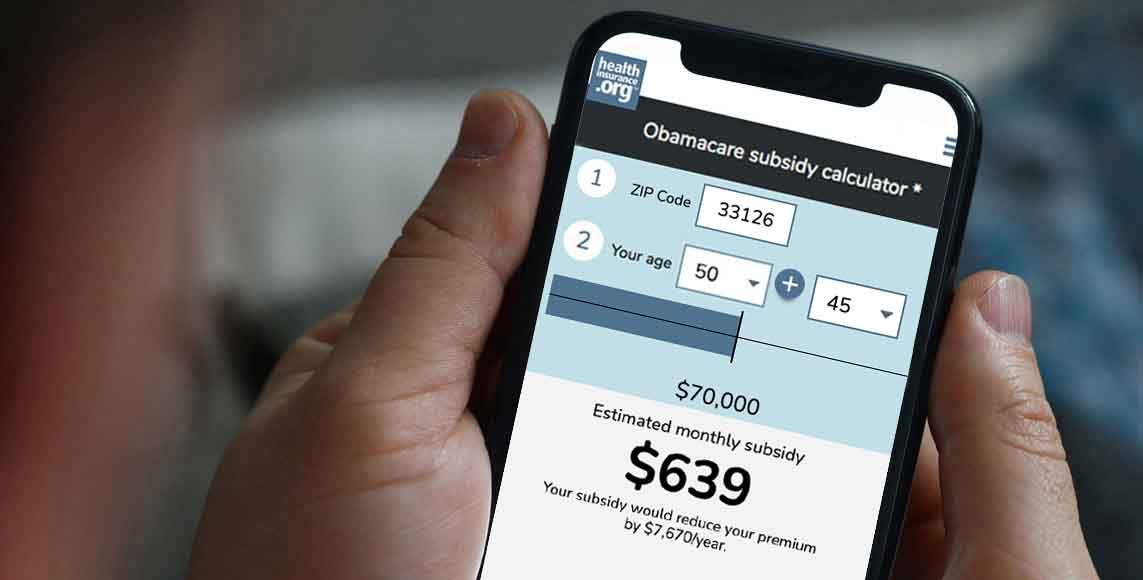

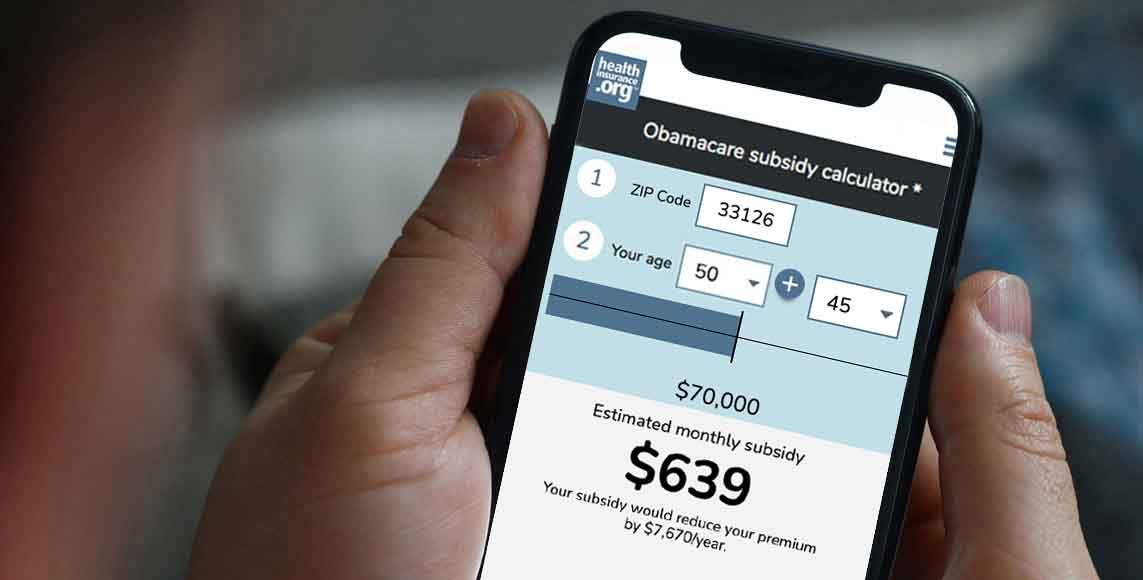

Provide information above to get an estimate.

Provide information above to get an estimate.

The ARP and IRA include several provisions that make health insurance and health care more accessible and affordable.

(There were some additional provisions in the ARP that were temporary and have not been extended: For 2021, it ensured that people receiving unemployment compensation were able to enroll in a Silver plan with $0 premiums and robust cost-sharing reductions. And for the 2020 plan/tax year, it ensured that people who would otherwise have had to repay excess premium subsidies to the IRS did not have to do so.)

The ACA’s health insurance premium subsidies – also known as premium tax credits – normally adjust each year to keep pace with premiums. (Here’s how that works.)

For 2021 through 2025, subsidies are more robust than they usually are. There is no “subsidy cliff” for these five years. Instead, nobody purchasing coverage through the Marketplace has to pay more than 8.5% of their household income (an ACA-specific calculation) for the benchmark silver plan. And people with lower incomes pay a smaller-than-normal percentage of their income for the benchmark plan – as low as $0 for people with income that doesn’t exceed 150% of the poverty level.

In addition to the extra subsidies under the ARP and IRA, subsidy amounts were already considerably larger than they were before 2018. This has been the case since the Trump administration stopped funding cost-sharing reductions (CSR – a different type of ACA subsidy) in the fall of 2017.

To cover the cost, insurers in most states now add the cost of CSR to Silver plan premiums. That makes the Silver plans disproportionately expensive, and since premium subsidies are based on the cost of the benchmark Silver plan, it also makes the premium subsidies disproportionately large.

Premium subsidies can be used to offset the premiums for any metal-level plan in the exchange. Because the subsidies are so large, some enrollees can get $0 premium Bronze plans, or even $0 premium Gold plans. According to an analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation, 5 million uninsured Americans were eligible for free Marketplace plans in 2023. Depending on their income, these could be Bronze, Silver (including CSR-enhanced Silver), or Gold plans. 1

More than 21.4 million people enrolled in Marketplace plans during the open enrollment period for 2024, and more than 19.7 million of them were receiving premium subsidies. 2

For those enrollees, premium subsidies covered the bulk of their premiums: The average full-price premium was $605/month, and the average premium subsidy was $536/month. The overall average after-subsidy premium (including people who didn’t get a subsidy at all) was just $111/month. 2

In short, the subsidies are a significant part of the “affordable” portion of the Affordable Care Act. With each successive open enrollment period, awareness of the law’s premium tax credits (subsidies) has continued to grow. But many Americans may still be wondering, “Am I eligible to receive a premium subsidy – and if so, what should I expect?” This is particularly true through 2025, as the American Rescue Plan and Inflation Reduction Act make coverage much more affordable for millions of people.

Subsidy eligibility is based on income (ACA-specific MAGI). To qualify for a subsidy, a household must have an income of at least 100% of the federal poverty level (or above 138% of the federal poverty level in states that have expanded Medicaid). And although there is normally an income cap of 400% of the poverty level (discussed in more detail below), that does not apply from 2021 through 2025. Instead, subsidy eligibility is based on the cost of the benchmark plan relative to the person’s income. If it’s more than 8.5% of the person’s income (or a lower percentage, for people with lower incomes), a subsidy is generally available.

But in addition to income, there are other factors that determine eligibility for premium subsidies. Let’s take a look at what they are:

If your employer offers coverage that’s considered affordable and provides minimum value, you’re not eligible to receive a subsidy in the exchange. The family glitch previously caused some families to be ineligible for subsidies due to the way affordability of employer-sponsored health plans is calculated, but the IRS fixed the glitch in the fall of 2022, meaning that some families became newly eligible for Marketplace subsidies in 2023.

If your employer offers affordable coverage that provides minimum value, you already are receiving a subsidy from your employer in the form of pre-tax health insurance benefits and an employer contribution to your premiums. The exchanges are designed to offer subsidized health insurance benefits to people who are self-employed, retired before age 65, and people who work for a company that does not offer affordable health benefits.

Note that some employers offer coverage that is either not affordable or does not provide minimum value (by doing this, they can avoid the potentially larger penalty they would pay if they didn’t offer coverage at all). These plans, while technically considered minimum essential coverage, can be quite skimpy – and to clarify, large employers are subject to a penalty if they offer these plans and their employers opt for a subsidized plan in the exchange instead. If your employer offers a plan that doesn’t meet the affordability rules and/or the minimum value rules, you do have access to premium subsidies in the exchange if you’re otherwise eligible based on your income, immigration status, etc.

Premium subsidies aren’t available to people who qualify for Medicaid or CHIP, since Medicaid and CHIP (the Children’s Health Insurance Program) generally provide even more financial assistance than premium subsidies.

It’s important to understand that CHIP eligibility extends to much higher incomes than Medicaid eligibility. Kids in households with MAGI at 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL) are eligible for CHIP in nearly every state, and there are several states where CHIP eligibility extends to above 300% of the poverty level.

If your kids are eligible for CHIP, they aren’t eligible for premium subsidies. That means the subsidy amount you’ll see when you enroll is just for the adults in your household, as the kids will be on CHIP instead.

There’s no upper age limit for subsidy eligibility. But most people become eligible for premium-free Medicare Part A when they turn 65. In that case, they lose their eligibility for premium subsidies.

But if you’re not eligible for premium-free Medicare Part A because you don’t have enough work history in the U.S., you can continue to buy coverage in the exchange, and you’ll continue to receive premium subsidies if your income makes you eligible. (See question A6 in this guide from CMS.)

Premium subsidies aren’t available to people with income below the poverty level (with the exception of recent immigrants, as described below). This is because when the ACA was written, it was expected that everyone living in poverty would be eligible for Medicaid. But two years after the law was enacted, the Supreme Court ruled that states couldn’t be forced to expand Medicaid, and some states still haven’t expanded coverage.

This results in a coverage gap for people with income below the poverty level in those states. In most cases, they’re not eligible for Medicaid because they’re in states with strict Medicaid eligibility guidelines. But they’re also not eligible for premium subsidies. As of 2024, this applies to people in nine states.

Premium subsidies aren’t available to people who aren’t in the U.S. legally, although they are available to immigrants who are lawfully present in the U.S. And starting in November 2024, for coverage effective in 2025, DACA recipients can enroll in Marketplace plans and qualify for income-based subsidies.

In other words, you don’t have to be a U.S. citizen to get premium subsidies. In fact, premium subsidies are available for recent immigrants with income below the poverty level, even though they’re not available to the general population with income below the poverty level.

That’s because in most states, Medicaid is not available to recent immigrants until they’ve been in the U.S. for at least five years. When the ACA was written, the expectation was that Medicaid would be expanded in every state to cover people living in poverty.

But lawmakers knew recent immigrants wouldn’t be eligible for Medicaid, even with the expanded eligibility guidelines. So they were careful to clarify that these individuals would be able to receive premium subsidies in the exchange. (Their goal was to make it so that all lawfully present U.S. residents would have access to affordable coverage, one way or the other.)

A note about state-run exchanges and undocumented immigrants: Washington’s health insurance exchange received federal approval to allow undocumented immigrants to enroll as of 2024, and Washington allows those enrollees to qualify for state-funded subsidies. Colorado debuted a separate enrollment platform in the fall of 2022, which allows undocumented immigrants to enroll in coverage with state-funded subsidies. In the rest of the country, undocumented immigrants cannot use the exchange at all. And federal subsidies are never available for undocumented immigrants.

Premium subsidies normally aren’t available to people with income (ACA-specific MAGI) above 400% of FPL. As noted above, however, that’s not the case for 2021 through 2025, due to the American Rescue Plan and the Inflation Reduction Act.

When the ACA was written, the expectation was that coverage would be affordable without subsidies at that income level. But as premiums have grown, there are some areas of the country where coverage can easily exceed 25% of household income for a family just a little above 400% of the poverty level. (For 2021 coverage, before the American Rescue Plan removed the upper income limit for subsidy eligibility, it was $51,040 for a single person and $104,800 for a family of four.)

The number of people with off-exchange coverage – and unsubsidized coverage in general, including people who buy full-price plans in the exchange – has declined precipitously in many areas. This is not surprising given the sharp premium increases in 2017 and 2018, which caused coverage to become unaffordable for some people who earned a little too much to qualify for subsidies. But from 2021 to 2025, Marketplace enrollees don’t have to pay more than 8.5% of their household income for the second-lowest-cost Silver plan, regardless of how high their income is. This helps to ensure that coverage is affordable even for older enrollees (whose coverage is more expensive) and enrollees in areas where health insurance is more expensive than average.

It’s important to understand that contributions to a health savings account (HSA) and/or pre-tax retirement plans will reduce your income for subsidy-eligibility purposes. This is still true from 2021 through 2025 – even though there is no subsidy cliff for those years, it’s still possible to reduce your ACA-specific MAGI (and thus qualify for a more significant subsidy) by making pre-tax retirement plan contributions or HSA contributions.

Even with the ARP and IRA in place, there won’t be subsidies for people earning millions of dollars, as health insurance premiums won’t even come close to eating up 8.5% of their income. But people with income well above 400% of the poverty level do now qualify for subsidies in some areas.

Now that we know who is eligible, let’s take a look at how the subsidies work. The subsidies are tax credits that help middle-income and low-income people afford health insurance when they don’t have access to affordable employer-sponsored coverage or government-sponsored coverage (typically Medicaid/CHIP or Medicare). Most eligible enrollees take those tax credits in advance, paid directly to their health insurance carrier each month to offset the amount that has to be paid in premiums.

But you can also pay full price throughout the year for a plan through the exchange, and then claim your subsidy as a lump sum when you file your taxes. Subsidy reconciliation is completed when you file taxes, using Form 8962. If the subsidy you receive during the year is too high, you’ll pay back some or all of it when you file taxes. (Note that for 2020 only, people did not have to repay excess premium subsidies; this was a provision in the American Rescue Plan). If it was too low – or if you didn’t receive an advance subsidy at all during the year – you’ll get the balance of the tax credit when your return is processed.

As discussed above, premium subsidies are available to exchange enrollees based on their ACA-specific MAGI. People enrolled in off-exchange plans are not eligible for subsidies, regardless of income, and cannot receive any premium tax credits when they file their tax returns. This is true even if an identical version of their plan is also sold on-exchange. So it’s essential to enroll via the exchange in your state if you want to take advantage of the available tax credits.

In states that have expanded Medicaid under the ACA, Medicaid is available to enrollees with incomes up to 138% of the poverty level, and subsidies are not available below that threshold. (In Washington DC, Medicaid is available up to 215% FPL. In Minnesota and Oregon, Basic Health Program coverage is available up to 200% FPL. And in New York, Basic Health Program coverage is available up to 250% FPL. So your income has to be above those levels in those states to qualify for premium tax credits.)

Although there is no upper income limit for subsidy availability from 2021 through 2025, it’s important to understand that in other years, the upper income limit for subsidy eligibility is higher in Alaska and Hawaii than it is in the rest of the country. That’s because Alaska and Hawaii have higher poverty levels, meaning that 400% of the poverty level is a higher dollar amount in those states. And even while the ARP/IRA rules are in place, two people with equal income — one in Alaska or Hawaii and one in the continental US — will find that their income puts them at different percentages of the federal poverty level, which is used to determine the percentage of income that you have to pay for your coverage.

Note that some people with MAGI under 400% of the poverty level don’t receive subsidies simply because the unsubsidized cost of coverage in their area is under the threshold established by the ACA. This may still be true in some cases for very young adults even with the ARP/IRA in place, but it’s even less common now than it was before the subsidies were enhanced under those laws.

Subsidies are tied to the cost of the second-least expensive Silver plan in your area (ie, the benchmark plan). The architects of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) wanted to make sure that people who must buy their own insurance can afford that benchmark Silver plan, even in regions where health care is extremely expensive. So knowing the price of the benchmark plan in your region is key to calculating the size of your subsidy.

The benchmark can be a different plan from one year to the next, as insurers adjust their prices – but it’s always the second-lowest-cost Silver plan in a given area. (Note that the cost of the benchmark plan is specific to each person’s circumstances. It depends on your zip code and the age of any family members who are applying for coverage, so the cost of the benchmark for your household will not be the same as the cost of the benchmark for another household. This is generally true even if you live next door to each other, since the ages of each household’s members are likely to be different).

As the cost of the benchmark plan changes, the size of the premium subsidy changes too, to keep pace with the benchmark plan cost. If the benchmark rate goes up for the coming year, subsidies increase. But if the benchmark rate goes down, premium subsidies will decline. This has happened quite often recently, especially in areas where new insurers join the exchange.

For 2022, a lot of new insurers joined the exchanges across the country. For 2023, there were again a lot of insurers that joined the exchanges. And although there were also some exits, the number of insurers offering plans through HealthCare.gov is higher for 2023 than it was for 2022. For 2024, new insurers joined the exchanges in several states, including California, Colorado, Delaware, Indiana, Nevada, New Mexico, and Oklahoma. This article is a detailed description of how insurers joining the exchange can affect premium subsidies, and this article provides several examples of how a plan change can offset the effects of decreasing subsidy amounts.

Anytime there are changes like this — whether insurers are entering or exiting the marketplace — it can affect which plan holds the benchmark spot and how much people will receive in subsidies. So it’s always important to actively shop around during open enrollment to find the plan that represents the best value.

The enrollment software will automatically calculate your subsidy, but many enrollees are curious about how the subsidy amount is determined, so here are the details:

The size of your subsidy is based on how your household’s income (ACA-specific MAGI) compares with the prior year’s poverty level, and the price of the benchmark Silver plan in your region.

1) Determine your household’s ACA-specific Modified Adjusted Gross Income. If you need help with this, you can use our calculator:

Use this to calculate your household’s estimated yearly income. Consider including your income, your spouse’s income, and that of any tax dependents, all of which are usually counted by the Marketplace. After that, provide information about expenses that may be deducted.

This calculator is for educational and illustrative purposes only and should not be construed as financial or tax advice. It uses the income and other information you provide. We included categories of income and expenses that the Marketplace commonly (but not always) uses. You should contact a tax advisor or other professional about any specific requirements or concerns.

Your Estimated Yearly Income:Click calculate to see updated yearly income

Deduction type* Deduction start date (in coverage year) Deduction end date (in coverage year)2) Use the table below to find out where your income falls in relation to the federal poverty level. You’ll be looking at your projected 2024 income, but you’ll be comparing it to the 2023 federal poverty level, which is what the numbers in this table represent. (Since open enrollment for 2024 took place before the poverty level numbers for 2024 were available, these numbers will be used for all plans with 2024 effective dates.) As noted above, the numbers are higher in Alaska and Hawaii.

(Here are the 2024 federal poverty level numbers, which will be used to calculate premium subsidy amounts for 2025 coverage.)

Normally, an income above 400% of the poverty level would make a household ineligible for premium subsidies. But from 2021 through 2025, premium subsidies are available above that level if they’re necessary to keep the cost of the benchmark plan at no more than 8.5% of the household’s ACA-specific MAGI.

In most states, if your income doesn’t exceed 138% of the poverty level, you’ll be eligible for Medicaid. The other delineations are for determining the percentage of income that you’d be expected to pay for the benchmark plan in the exchange, as described in the next step.

| Percent of 2023 Federal Poverty Level (FPL) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household Size | 100% | 138% | 150% | 200% | 300% | 400% |

| 1 | $14,580 | $20,120 | $21,870 | $29,160 | $43,740 | $58,320 |

| 2 | $19,720 | $27,214 | $29,580 | $39,440 | $59,160 | $78,880 |

| 3 | $24,860 | $34,307 | $37,290 | $49,720 | $74,580 | $99,440 |

| 4 | $30,000 | $41,400 | $45,000 | $60,000 | $90,000 | $120,000 |

| 5 | $35,140 | $48,493 | $52,710 | $70,280 | $105,420 | $140,560 |

| 6 | $40,280 | $55,586 | $60,420 | $80,560 | $120,840 | $161,120 |

| For each additional person, add | $5,140 | $7,093 | $7,710 | $10,280 | $15,420 | $20,560 |

3) Find out how much the Affordable Care Act expects you to contribute to the cost of your insurance by consulting Table 2. The expected contribution is normally adjusted slightly each year. The percentages listed below are for 2021 through 2025, and are specific to Section 9661 of the American Rescue Plan (the IRS had previously issued a normal contribution percentage table for 2021, but it’s no longer relevant; all of the expected contributions have been adjusted down as a result of the ARP, and these same percentages will continue to be used through 2025, under the Inflation Reduction Act).

| If you earn | Your expected contribution is |

|---|---|

| Up to 150% of FPL | 0% of your income (ie, the benchmark plan will have no premium) |

| 150%-200% of FPL | 0%-2% of your income |

| 200%-250% of FPL | 2%-4% of your income |

| 250%-300% of FPL | 4%-6% of your income |

| 300%-400% of FPL | 6%-8.5% of your income |

| 400% of FPL or higher | 8.5% of your income |

The subsidy will make up the difference between the amount an individual is expected to contribute (based on income) and the actual cost of the area’s second-lowest-cost Silver plan.

4) Determine how much a benchmark Silver plan costs in the area where you live. You can scroll through the available quotes in your state’s exchange and see what the second-lowest-cost Silver plan’s premium would be for you and your family, or you can call the exchange. In most states, these numbers start to become available by mid-late October, in advance of the November 1 start to open enrollment.

It’s important to note that the benchmark plan changes from one year to another: Carrier A might have the second-lowest-cost Silver plan one year, but due to premium fluctuations, Carrier B might take over that spot the following year. Here’s an example of how this works.

5) See Table 2. Subtract the amount that you are expected to contribute (based on your income) from the cost of your benchmark Silver plan. For instance, let’s say your Silver plan costs $6,000 a year, and you are expected to contribute $1,000. You will receive a subsidy of $5,000.

This spreadsheet shows several scenarios – different ages, income levels, and locations – with after-subsidy benchmark and lowest-cost plan prices under the American Rescue Plan in 2021. And you can see the corresponding amounts without the ARP, to see how much more affordable the ARP made coverage as of 2021.

Let’s work through a specific example for 2024, so that you can see exactly how it works (we’re rounding numbers here to make it easy to follow; the exact dollar amounts would be slightly different):

Rick is 27 and lives in Birmingham, Alabama (zip code 35213). According to HealthCare.gov, the benchmark plan for Rick has a full-price premium of about $464 per month in 2023.

If Rick earns $29,160 (that’s 200% of FPL, based on the 2023 FPL numbers) he would be expected to kick in 2% of his income, or about $583 in 2024, towards the cost of the benchmark plan (0.02 x $29,160 = roughly $583), with a subsidy covering the rest of the premium. That amounts to about $48 per month in premiums that Rick would have to pay himself if he buys the benchmark plan. A subsidy of about $416/month will cover the rest of the cost.

It’s important to understand that without the American Rescue Plan, Rick would have been expected to pay 6.52% of his income for the benchmark plan in 2021, and a similar percentage each year since then. This would have amounted to about $1,900 that Rick would have had to pay for the benchmark plan in 2024 (that’s an approximation, as the specific percentage used to be inflation-adjusted each year). So the American Rescue Plan’s adjustments to the subsidy calculations have increased Rick’s subsidy amount by somewhere around $1,300 in 2024, or about $110/month (the subsidy had to grow by roughly $1,300 for the year to bring Rick’s expected contribution down from around 6.5% of his income to just 2% of his income).

To calculate his subsidy, he just needs to subtract $583 (the amount he kicks in over the course of 2024) from $5,570 (the total cost of the benchmark plan over the course of 2024). His subsidy will be about $4,987 for the year. That means the exchange will send about $416/month to his insurer, and Rick will have to pay the other $48/month.

Of course, that’s assuming he picks the benchmark plan; if he buys a less-expensive plan, he’ll pay less, and if he buys a more expensive plan, he’ll pay more. The $416/month subsidy will stay the same regardless of what plan he buys – unless he enrolls in one of the eight available plans that have full-price premiums of less than $416/month. In that case, the subsidy will cover the full price and his monthly premium will be $0, but he won’t be able to claim the excess subsidy.

(Note that you can also calculate your expected contribution percentage if your income is somewhere in the middle of one of the ranges shown in Table 2. Here’s how it works.)

Rick’s 27-year-old cousin Alice, earns the same amount as Rick, but lives in Little Rock, Arkansas (zip code 72201), where the pre-subsidy cost of the benchmark plan is quite a bit lower. After her subsidy, she’ll pay the same amount as Rick for the benchmark plan (because they earn the same income), but her subsidy won’t need to be as large. The benchmark plan for Alice has a full-price premium of $350 per month in 2024, according to HealthCare.gov’s plan comparison tool.

If Alice also earns $29,160 (200% of the FPL) the government would expect her to spend 2% of her income on the benchmark plan, just like her cousin in Alabama. (Remember, the expected contribution is tied to income (MAGI), not the underlying cost of the plan.) So she, too, would have to pay $583 of her own money (about $48/month) to buy the benchmark plan in her area. But because the full price of the benchmark plan for Alice would only be $4,200 over the course of 2024, her subsidy will only need to be about $3,600 (or about $300/month).

Since Rick and Alice earn the same amount, they pay the same in after-subsidy costs for the benchmark plan: About $583 for the year. This is based on their MAGI – not their age, health status, or location. But Rick’s subsidy has to be larger than Alice’s, because the unsubsidized cost of his plan is so much more, due to his location.

If Rick and Alice were younger, the Silver plan would be less expensive and their subsidies would be smaller. If they were older, the Silver plan would be more expensive, and their subsidies would be higher.

The idea behind the subsidies is to level the playing field and bring average premiums to a middle ground for everyone who has the same general level of income (MAGI). So at the same income level, an older person will receive a higher subsidy than a younger person, but they’ll both ultimately pay the same price for the benchmark plan.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.