Adrenal lesions are very common.

Many of these lesions are incidentally discovered and called incidentalomas.

An adrenal incidentaloma is defined as a mass > 1 cm that is detected on imaging exams not performed for suspected adrenal disease.

Most of these incidentalomas are benign non-functioning adenomas even in patients with a known malignancy.

In this article we will discuss the evaluation and management of adrenal masses by dividing them into:

Adrenal incidentalomas are common and seen in about 3% of abdominal CT's, increasing up to 10% in elderly patients [1,2,3].

The issue is to differentiate benign adrenal tumors from metastases or primary malignant masses without unnecessarily exposing the majority of patients to the burden of clinical workup, interventions and imaging follow-up.

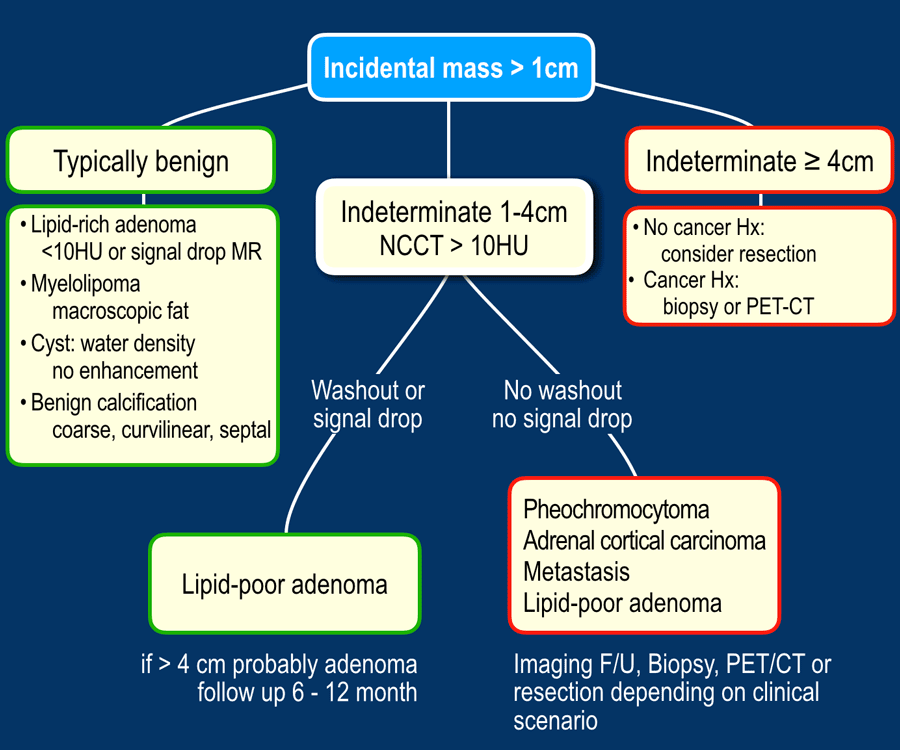

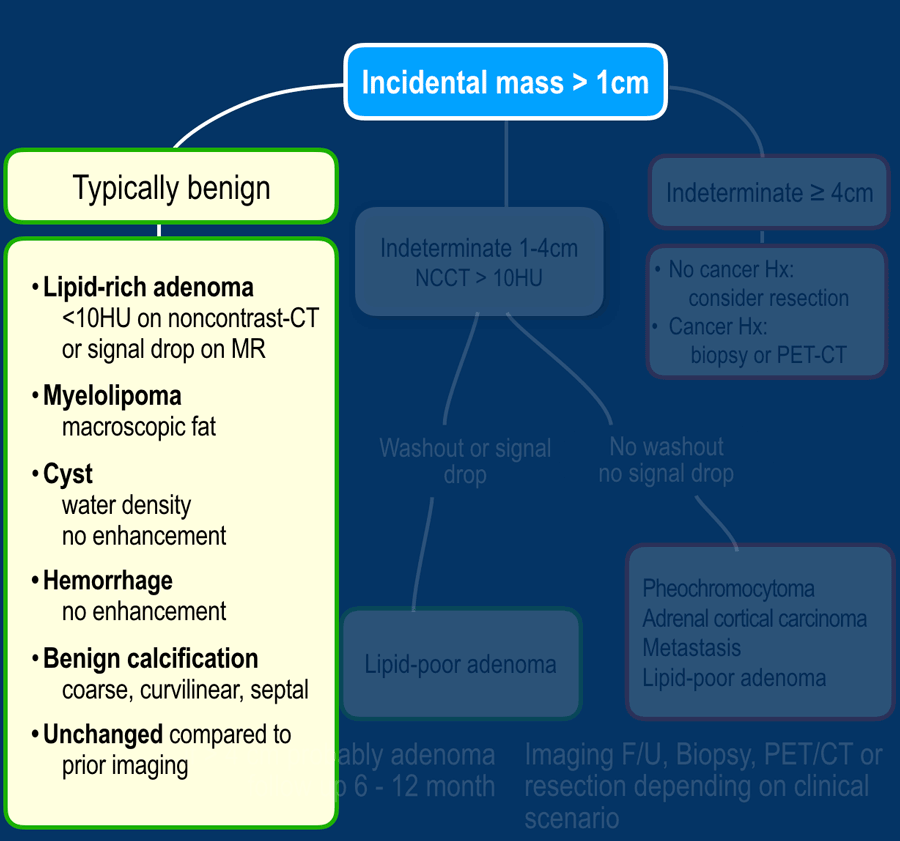

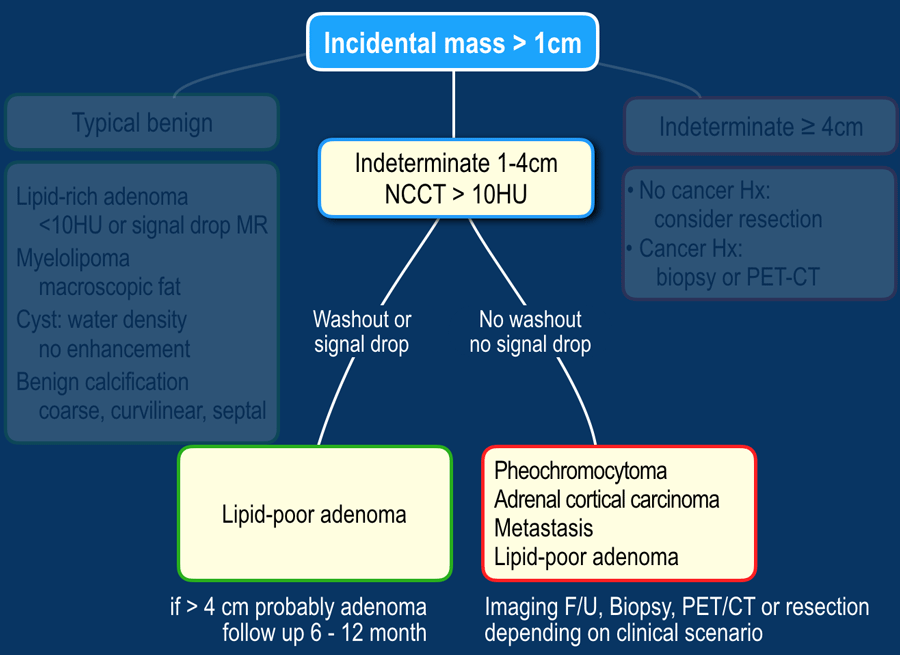

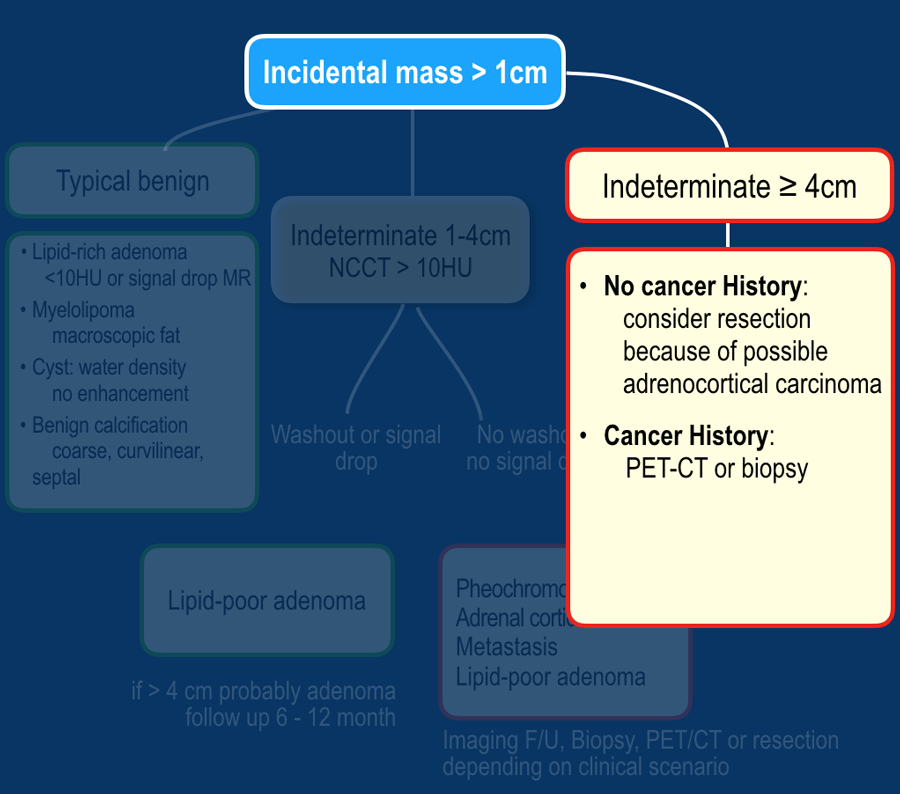

First, determine whether a lesion has typically benign or indeterminate imaging features.

If it is indeterminate, do a washout-CT or an MRI to see whether it is a lipid-poor adenoma.

If it is not an adenoma, then you have to choose between follow up, PET-CT, biopsy or resection.

When an adrenal incidentaloma is detected, use the following steps:

We will now discuss each of these possibilities.

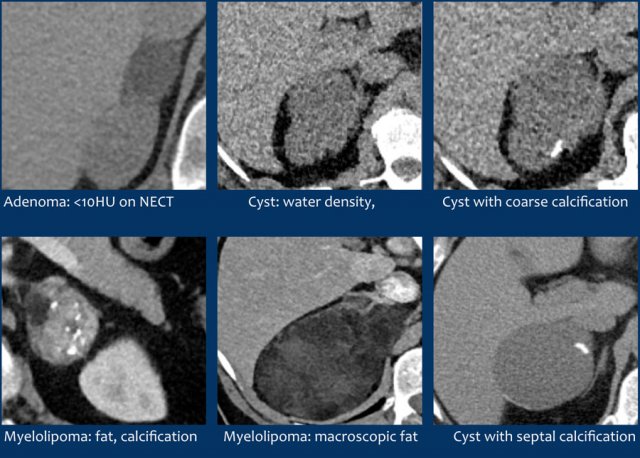

Many adrenal lesions can be categorized as typically benign and need no follow up (table):

'No enhancement' is defined as less than 10HU difference between the unenhanced and enhanced CT.

Here some examples of typically benign lesions.

Lipid-rich adenoma

70% of adenomas contain high intracellular fat and will be of low attenuation on unenhanced CT [4,5].

A density equal to or below 10 HU is considered diagnostic of a lipid-rich adenomas.

Using a safe threshold value of 10HU on a native CT scan results in a sensitivity of 70-79% and a high specificity of 96-98% for the diagnosis of an adenoma [5-7].

30% of adrenal adenomas do not contain enough intracellular lipid to have a density of less than 10 HU and cannot be differentiated from non-adenomas on an unenhanced CT.

These adenomas are called lipid-poor.

They can be diagnosed with dedicated adrenal-CT to look for fast wash-out.

These lipid-poor adenomas will be discussed in the chapter on indeterminate lesions.

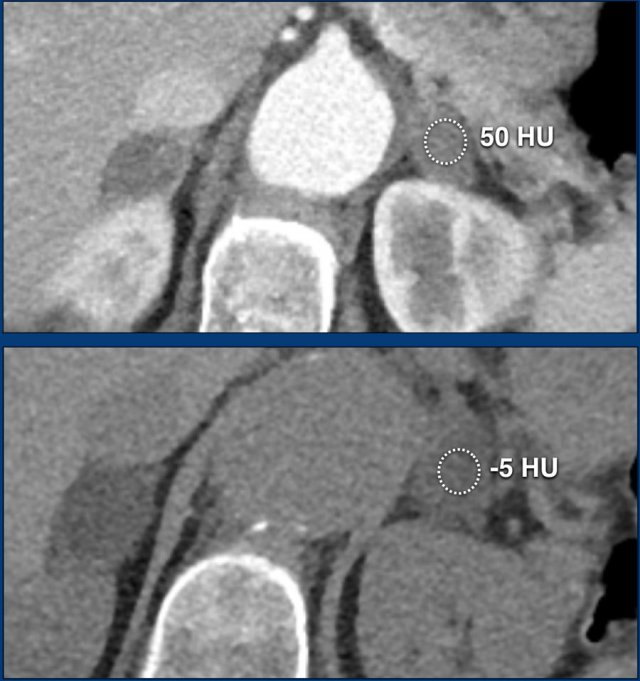

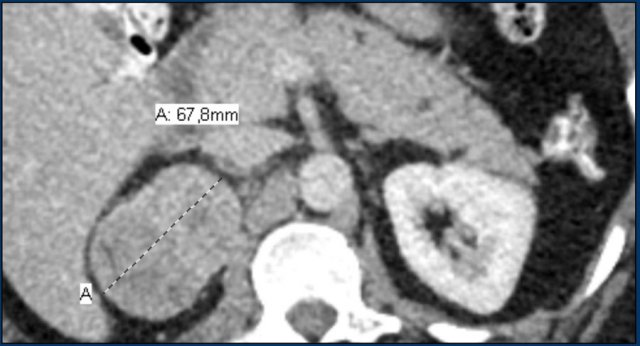

The images show bilateral adrenal incidentalomas found in a 64-year old patient scanned for analysis of an abdominal aneurysm.

The scan in the arterial phase shows bilateral lesions with a density of 50 HU.

On the non-enhanced CT performed a few days later, the density in both adrenal glands was less than 10 HU, proving these to be lipid-rich adenomas.

Cyst

An uncomplicated cyst is a well-defined lesion of water density that does not enhance.

A cyst has a thin wall and may have thin septa.

It may be an endothelial cyst or a pseudocyst, which are the most common, or a true epithelial or parasitic cyst (both rare) [5].

Pseudocysts may have thicker walls.

Hemorrhage or debris may cause increased internal attenuation.

Both benign and malignant tumors may show cystic degeneration and necrosis.

In those cases density measurements are unreliable.

Features of an underlying tumor may be an irregular thick wall of 5 mm or more and mural, septal or solid enhancement [5].

Lesions with benign calcifications

Lesions with benign calcifications

Coarse rounded, peripheral or septal calcifications are typically benign and may be seen in:

Bilateral calcifications also suggest a benign origin.

Punctate, dystrophic and irregular calcifiations are not typically benign and can be seen in:

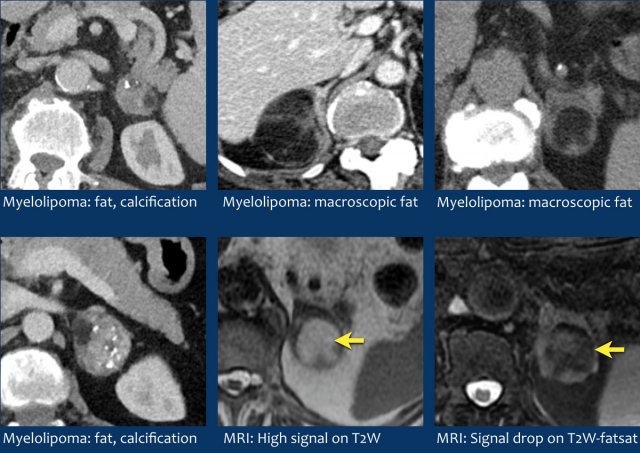

Myelolipoma

Myelolipomas are benign tumors composed of bone marrow elements.

Usually they are easy to recognize on CT or MR because they contain areas of macroscopic fat.

Calcifications are seen in 24% of cases.

The adrenal mass seen here on CT contains macroscopic fat, which is specific for the diagnosis myelolipoma.

On the right a different case with high SI on T1W-image indicating macroscopic fat in a myelolipoma.

CT image of another adrenal mass mainly composed of macroscopic fat.

Many adrenal lesions cannot be confidently diagnosed as either lipid-rich adenomas or another benign entity because the density is too high on the unenhanced CT or because there is only an enhanced CT to start with.

These lesions are called indeterminate.

These include the 30% of adenomas that are lipid-poor.

In order to find out if a lesion is a lipid-poor adenoma you can do a CT washout scan and look for rapid wash-out, or an MRI and look for signal drop on the out-of-phase scan.

Adenomas, both lipid-rich and lipid-poor, rapidly wash out contrast.

Non-adenomas, for instance metastases, generally enhance rapidly, but take longer to washout.

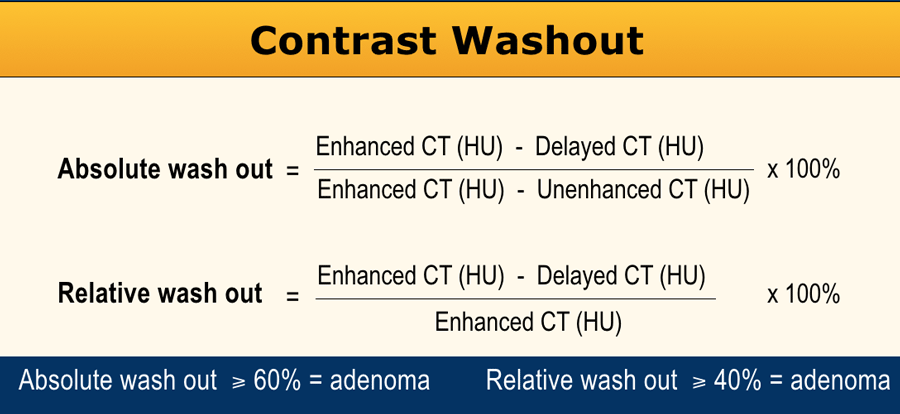

Absolute washout

A dedicated adrenal washout CT protocol consists of a non-contrast, a contrast -enhanced scan with a delay of 60-90 sec and a delayed scan at 15 minutes.

The ROI should encompass at least 2/3 of the lesion to ensure a representable assessment.

Absolute enhancement wash out ⩾ 60% is proof of an adenoma [5,6,8].

Relative washout

If an adrenal lesion is discovered on an enhanced scan while the patient is still on the table, then a second scan of the adrenals at 15 minutes after contrast injection can be made and the relative washout can be calculated.

Relative enhancement wash out ⩾ 40% is proof of an adenoma [5,6,8].

Adrenal washout pitfalls

Important exceptions to the washout rule are caused by tumors that show absolute and relative washout percentages within the adenoma-range, in decreasing order of occurence:

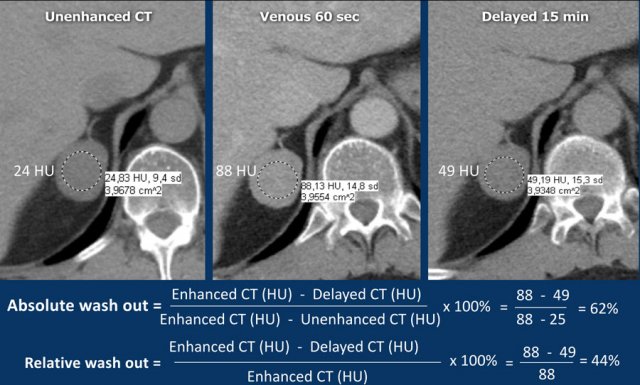

The images show an indeterminate lesion on the nonenhanced CT (density 24 HU).

The absolute washout in this patient is 62%.

This means that the lesion is a lipid-poor adenoma.

Usually adenomas show different enhancement compared to malignant lesions.

On an enhanced CT at 60 sec most adenomas show mild enhancement, while malignant tumors and pheochromocytomas show strong enhancement.

There is however too much overlap in enhancement to allow accurate differentiation between these lesions and that is why we need a wash-out CT scan.

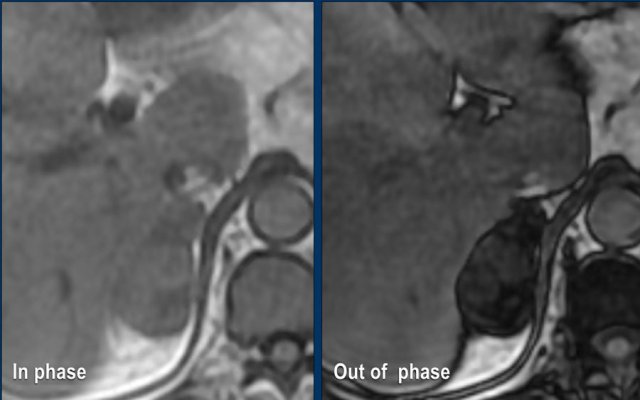

Lipid-poor adenomas can also be diagnosed with out-of-phase imaging.

They contain enough microscopic fat to cause a signal drop on out-of-phase imaging compared to in-phase imaging due to the chemical shift artefact.

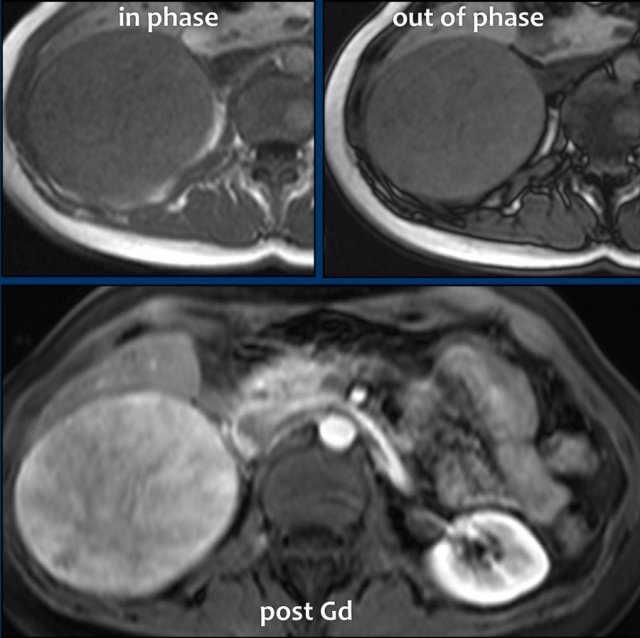

These images are of a 65- year-old female patient with an incidental discovery of a right adrenal mass on an abdominal ultrasound performed for renal stones.

The presence of microscopic fat is demonstrated by the signal drop on the opposed-phase image.

The patient was followed for 2 years, because the lesion is slightly inhomogeneous and measures 5.2 cm.

The lesion did not change in size and was not hormonally active.

It was diagnosed as a lipid-poor adenoma.

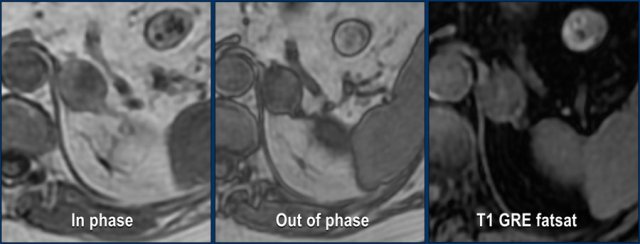

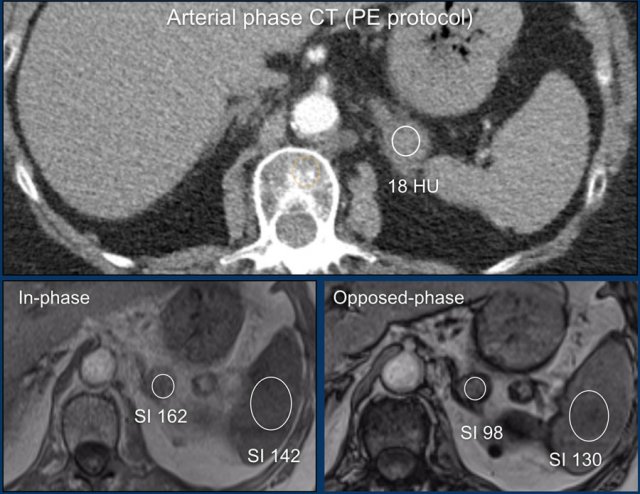

MRI performed for a left adrenal incidentaloma discovered on a non-contrast and arterial phase CT scan in a 61-year old male patient with an abdominal aneurysm.

On the non-contrast CT density was 18 HU.

T1 out-of phase image shows subtle inhomogeneous signal drop compared to in-phase.

Note that the fat-suppressed T1 does not help in the detection of microscopic intracellular fat.

Continue with next images.

The subtle central hyperintensity on the T1 fat sat is also hyperintense on the T2-weighted images and doesn't enhance on the post-contrast image.

After comparison with prior CT images from years before, the lesion turned out to be a slowly growing adenoma with recent internal hemorrhage.

The maximum diameter of the adrenal mass is predictive of malignancy.

In particular, lesions > 4 cm are more likely to be either metastases or adrenocortical carcinomas.

Adrenal mass size is important for two more reasons.

The overall prognosis is better for small adrenocortical carcinomas and smaller tumors are easier to resect by minimally invasive surgical techniques.

Therefore, the recommendation for an indeterminate adrenal mass > 4 cm in size and no history of cancer is surgical resection -in most cases without biopsy - in order to timely treat a possible primary adrenal cortical carcinoma [3,9].

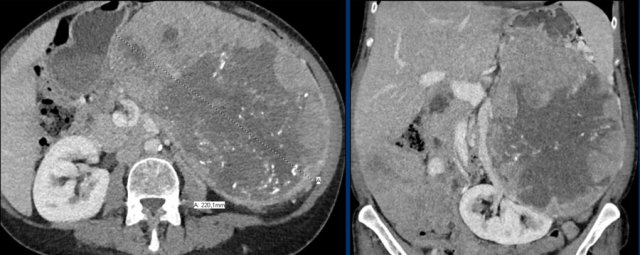

The next cases are examples of indeterminate lesions > 4 cm.

All were incidentally discovered in patients without a history of cancer.

All diagnoses were histologically proven and showed a wide variety of both benign and malignant tumors.

Metastasis of an adenocarcinoma

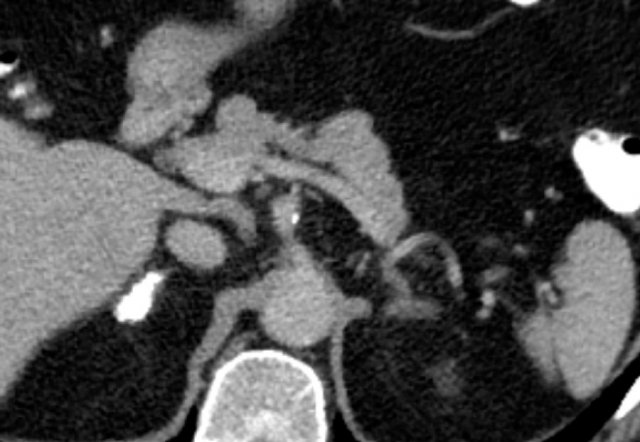

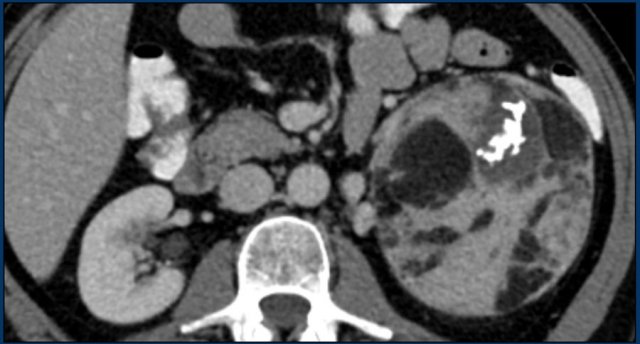

The image shows a heterogeneous ill-defined mass larger than 4 cm.

There is a hypo-enhancing center, which is probably the result of central necrosis.

In this particular case a biopsy was performed and revealed an adenocarcinoma, probably from primary lung carcinoma.

Surprisingly, extensive imaging analysis, including FDG PET-CT, did not detect a primary tumor, however.

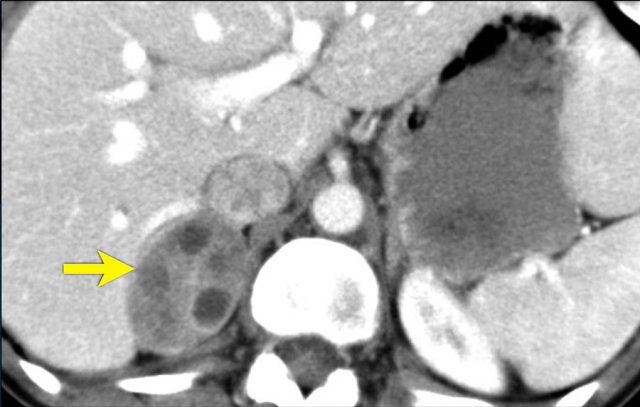

Adrenocortical carcinoma

The image shows a 67 mm heterogeneously enhancing relatively well defined lesion.

This proved to be an adrenocortical carcinoma, after resection.

Adrenal leiomyoma

The image shows a large indeterminate lesion with different densities and a partly calcified rim.

Biopsy revealed an adrenal leiomyoma.

The lesion was resected.

Pheochromocytoma

This is a heterogeneously enhancing, relatively well-defined indeterminate lesion.

It proved to be a pheochromocytoma.

Atypical adenoma

A 7cm hyperenhancing adrenal lesion with small cystic spots.

The lesion was resected because of its large size and indeterminate imaging features.

This proved to be an adenoma.

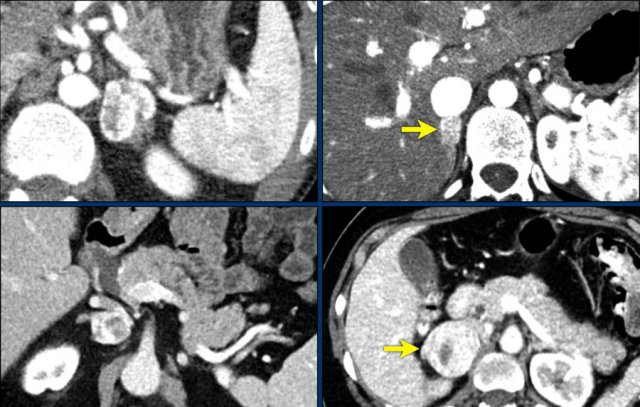

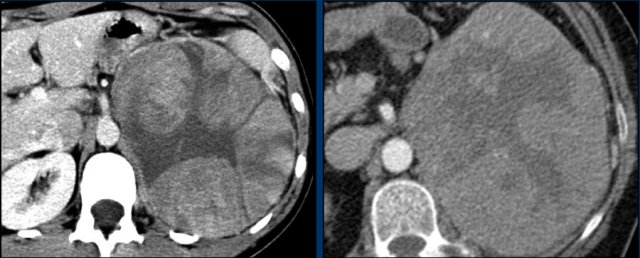

Pheochromocytomas: strong enhancement in all 4 cases, even in the smaller tumors

Pheochromocytomas are rare tumors that originate in the adrenal medulla.

Usually, tumors are larger than 3 cm when found.

Nonfunctioning tumors are typically larger than functioning tumors.

A typical pheochromocytoma will have an unenhanced density >10 HU, or higher in case of hemorrhage.

They are highly vascular, resulting in strong enhancement, but in contrast to adenomas they usually have delayed washout [4,5].

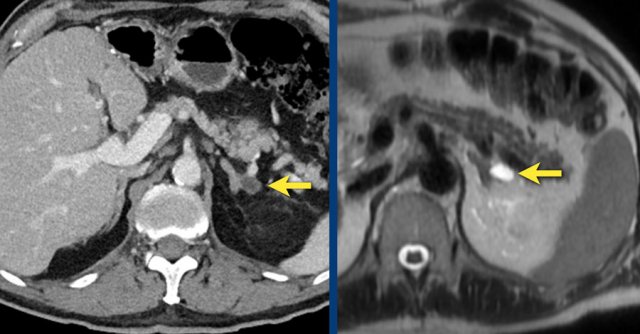

Pheochromocytoma with small cyst

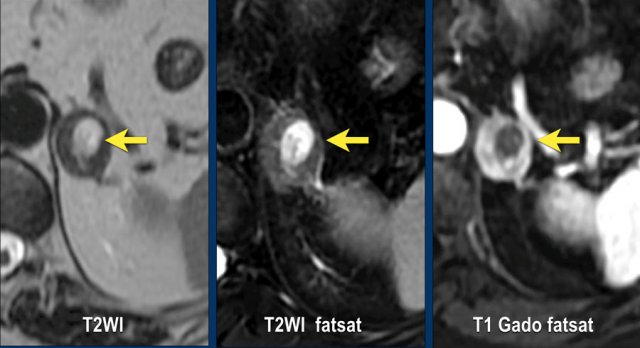

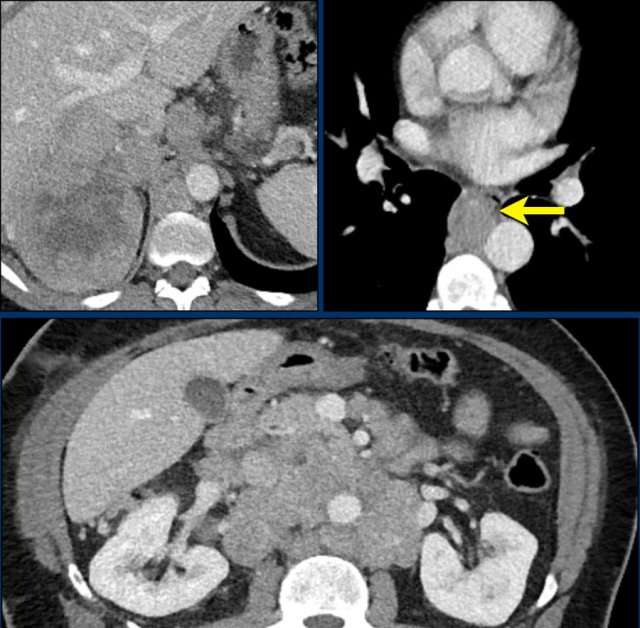

In 10% pheochromocytomas have calcifications and they frequently have multiple cysts (yellow arrows).

This image shows another pheochromocytoma with multiple cysts.

Larger tumors are prone to hemorrhage and necrosis, even when they are benign.

Pheochromocytomas are nicknamed "imaging chameleons" because many imaging features overlap with other tumors [5].

The so called classic "light bulb sign", which is homogeneous high signal intensity on T2W-images is seen in 65% of cases [4].

Imaging pitfalls

Because of these pitfalls diagnosis of pheochromocytoma is based on a combination of imaging features and is often supplemented by nuclear medicine imaging findings and biochemical confirmation.

10% tumor?

Pheochromocytomas have been called the "10% tumor" because it was considered that 10% were malignant, 10% bilateral, 10% familial, 10 % extra-adrenal and 10% occurred in children.

It has now become clear, however, that actually more than 30% of pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas are inherited [18].

Moreover, the percentage of tumors that are bilateral, extra-adrenal, pediatric or malignant differ with each specific hereditary syndrome [18].

Associated familial syndromes are multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type IIA/B, von Hippel-Lindau, neurofibromatosis type I, familial paragangliomas caused by SDH-gene mutations, Sturge-Weber syndrome and Carney triad [5, 18].

10 - 49% of pheochromocytomas are incidentally discovered in asymptomatic patients.

The radiologist should therefore have a low threshold in considering the diagnosis of a pheochromocytoma.

The biochemical diagnosis is made by measurement of plasma free or urinary fractionated metanephrines[2,18].

Unnecessary and potentially dangerous biopsy has to be avoided.

Myelolipomas

Adrenal myelolipomas are benign, relatively rare (0,08-0,2%) tumors that contain variable amounts of bone marrow elements and mature fat.

Myelolipomas are usually asymptomatic, unless they are very large (due to mass effect) or bleed [5].

The presence of macroscopic fat makes them easy to recognize on CT or MRI.

Attenuation on nonenhanced CT will be well below 0 HU.

At MR imaging the fatty portions will be hyperintense on non fat-saturated T1-weighted images and show signal dropout on fat-saturated T1 or T2-weighted images.

Calcifications are seen in approximately 24% of cases.

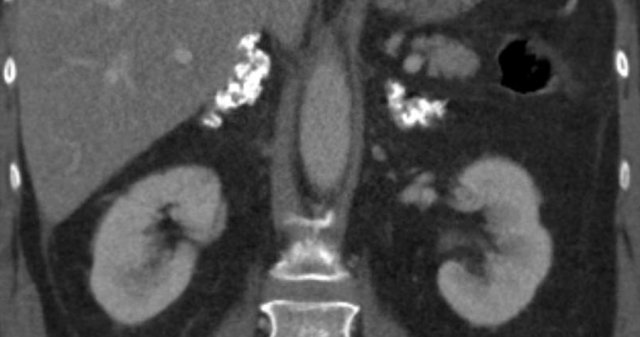

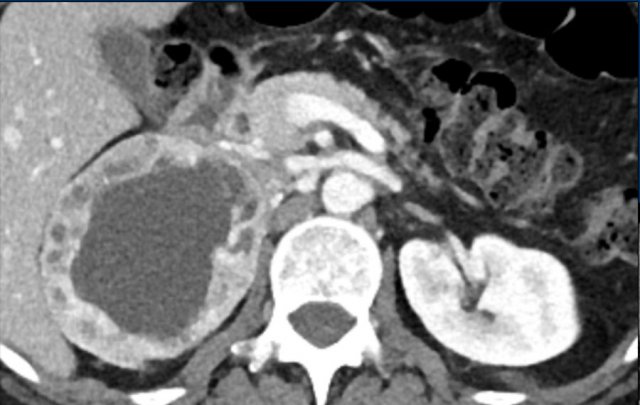

Axial and coronal image showing a large right myelolipoma with bleeding.

The image on the right is a follow-up scan.

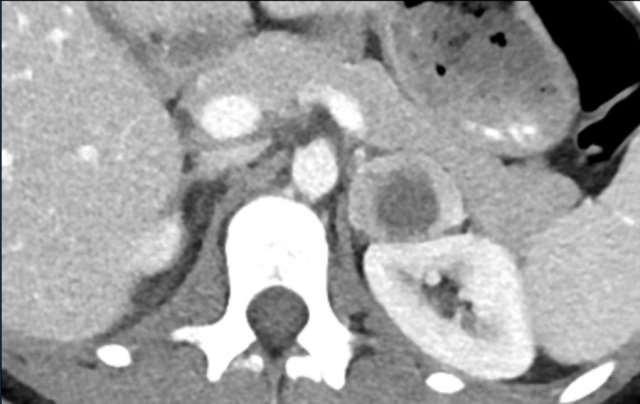

Here a small cyst is seen on CT and on a T2W-image.

Images show unenhanced and contrast-enhanced CT of a cyst.

The cyst is thin-walled, homogeneous and does not show any enhancement.

Adrenocortical carcinomas (ACCs) are rare aggressive tumors with an incidence of approximately 1-2 per million per year [5].

60% of ACCs are functioning.

Cushing's syndrome alone or a mixed Cushing's and virilisation syndrome are the most common presentation.

Virilisation, feminisation or hyperaldosteronism alone is rare (< 10%).

Patients with nonfunctioning adrenocortical carcinomas usually present with abdominal symptoms like nausea, vomiting, abdominal fullness, flank or back pain due to the large size of the tumor.

Adrenocortical carcinomas may be sporadic or associated with hereditary syndromes, including MEN1, Lynch syndrome, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and Li-Fraumeni syndrome.

Peak incidences are in early childhood and in the fourth and fifth decade of life [5].

Typical imaging features of adrenocortical carcinomas are [5,10]:

More than half of ACC patients have stage III or IV disease at the time of diagnosis, which explains the dismal prognosis of this diagnosis, with 5-year survival of 50% for stage III, and 15% for stage IV.

So, it is important to look for adjacent organ invasion, and for lymph node and distant metastases, most commonly in lung, liver or bone.

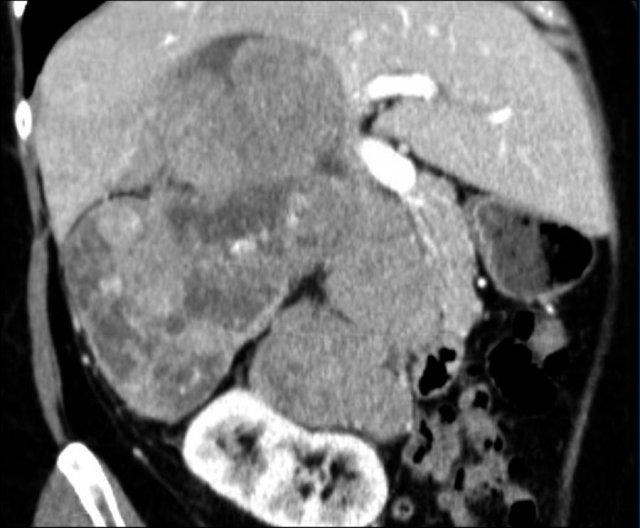

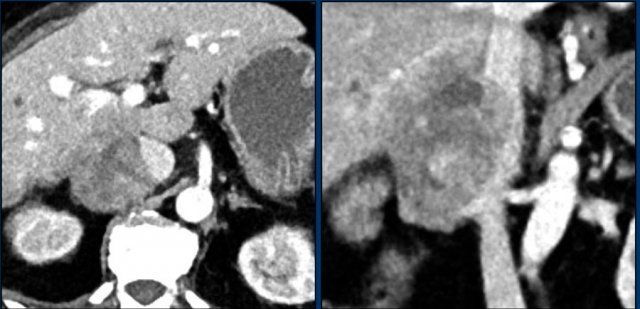

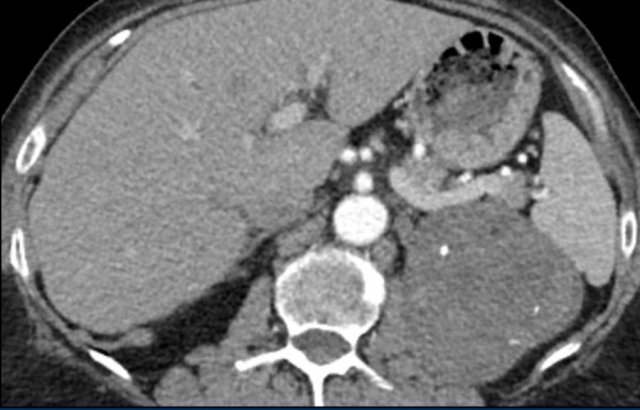

Here a typical example of an adrenocortical carcinoma.

The tumor is bulky and shows heterogeneous enhancement.

Note the 'stellar' central hypodensity.

There is capsular enhancement.

Small adrenocortical carcinomas have less typical features, but also enhance inhomogeneously.

Also note the dystrophic calcifications and areas of necrosis (red arrows).

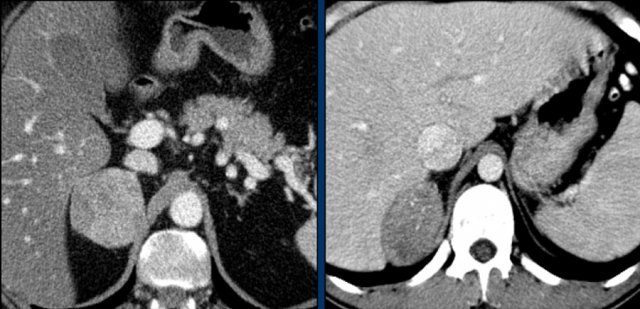

MRI-images of a 5.6 cm right adrenal carcinoma incidentally discovered on ultrasound.

Top row: mild T1W hypointensity, moderate T2W hyperintensity and intense hyperintensity on DWI.

Lower row:

Post contrast images show inhomogenous progressive enhancement with inhomogeneous progressive capsular enhancement in the portal and delayed phase.

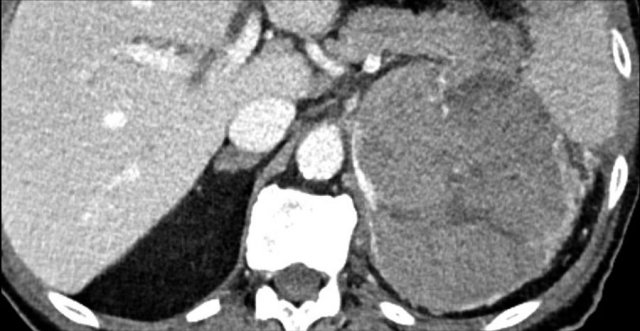

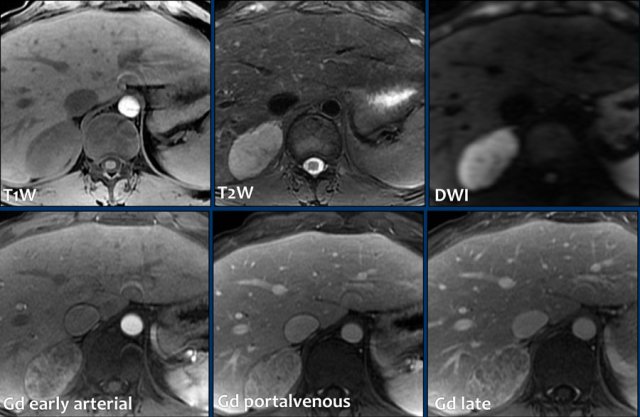

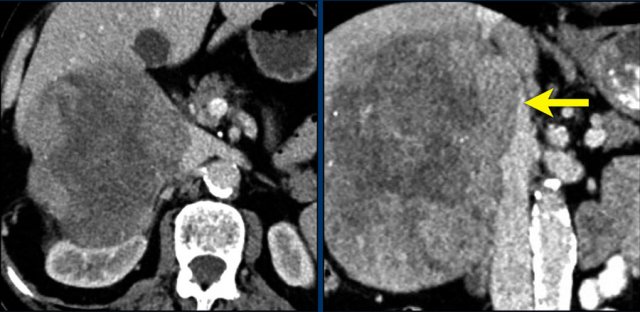

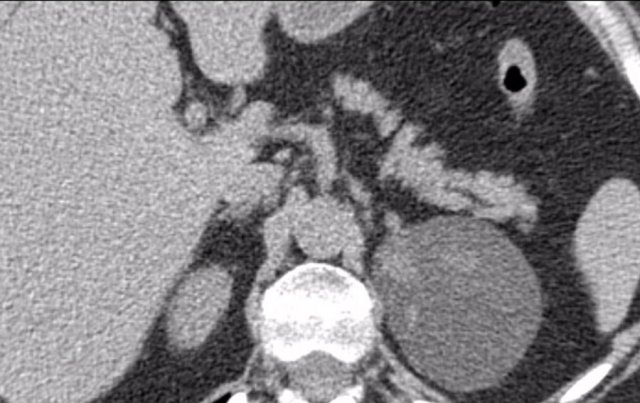

Axial and coronal CT images in a patients with a right adrenal carcinoma and extensive IVC invasion.

The coronal image also shows tumor extension into the right renal vein.

Axial and coronal CT images of another patient with an adrenal carcinoma with extensive IVC invasion (yellow arrow).

IVC and renal vein tumor invasion are seen in up to 20% of patients.

More than half of ACC patients have stage III or IV disease at the time of diagnosis with poor 5-year survival.

Here a large right adrenal adrenal carcinoma with extensive abdominal and mediastinal para-aortic lymph node metastases at the time of diagnosis.

Atypical adenoma

Lesions are considered atypical for adenoma if they show:

The following lesions were all resected because of large size, indeterminate radiological features or interval growth.

Here a 68 mm right hyperenhancing adrenal lesion with small calcifications and cystic spots, uncharacteristic for an adenoma.

Atypical adenoma with a post hemorrhagic pseudocyst

This is an enlarged left adrenal gland with a 6,4 cm well encapsulated hypodense, possibly cystic lesion, but with a density >10 HU. Histology showed an adenoma with a post hemorrhagic pseudocyst.

Atypical adenoma with hyperdense strands as a result of internal bleeding

The image shows a 7,6 cm left adrenal lesion with density < 0 HU, but with hyperdense strands.

On histology, this was shown to be due to internal bleeding in an adenoma.

Atypical adenoma with no signal drop and heterogeneous enhancement.

These images are of a very atypical large adenoma.

There is no signal drop on the opposed phase image.

The post contrast image shows heterogeneous enhancement.

On resection this proved to be an adenoma, however.

Oncocytoma of the left adrenal with fatty components.

Macroscopic fat is fairly specific for myelolipomas, but has also been described uncommonly in adenomas, adrenal teratomas, metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma, pheochromocytoma and even adrenocortical carcinoma.

If the macroscopic fat content exceeds 50%, the diagnosis of adrenal myelolipoma can be confidently made [4].

It is safe to follow-up incidentally discovered, asymptomatic adrenal myelolipomas.

Usually they are resected when they are larger than 7 cm, symptomatic (mass effect, pain), hormonally active or complicated by bleeding [5].

The image shows a fat-containing adrenal lesion, which is well-demarcated and contains soft tissue, fatty components and some calcifications. This lesion was removed because of its large size of 13 cm and uncertain origin.

It turned out to be an oncocytoma with fatty and myeloid metaplasia.

This is another very large adrenal lesion of uncertain origin with macroscopic fat and dystrophic calcifications.

This proved to be a liposarcoma with osteosarcomatous differentiation.

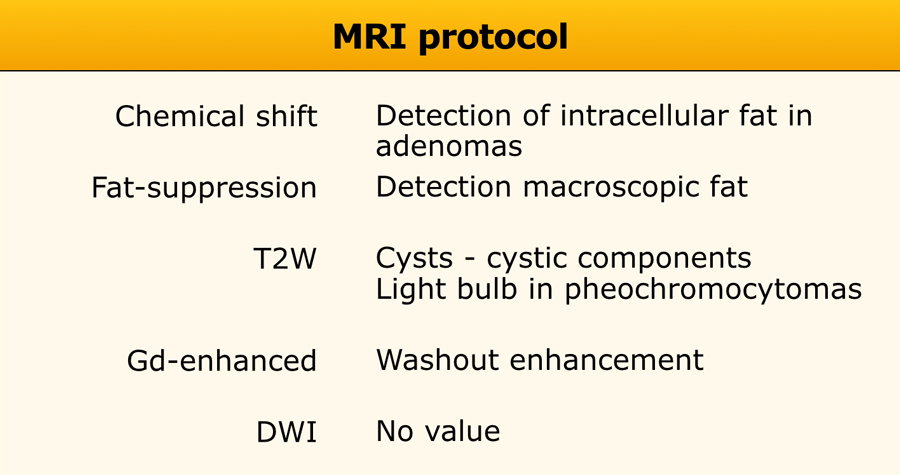

MRI is usually deployed as a problem solver after inconclusive CT or if contrast enhanced CT is contra-indicated.

MRI protocol should include [4,5]:

DWI has no added value due to considerable overlap in ADC values between benign and malignant adrenal lesions [11].

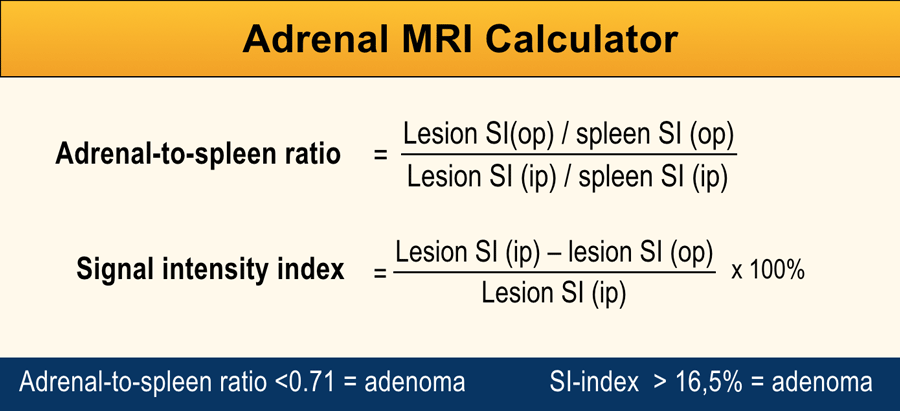

Most radiologists use visual evaluation to determine whether there is signal drop on out-of-phase images.

However, it is also possible to measure the change in signal intensity within a ROI placed over the adrenal lesion on the out-of-phase image and compare this to the in-phase image, using the spleen as internal reference organ.

Either the adrenal-to-spleen ratio (ASR) or the adrenal signal intensity index (SI-index) may be calculated by using the Adrenal MRI calculator [12,13].

An ASR 16.5% indicate an adrenal adenoma.

The reported sensitivity for ASR is 58 - 99% and the specificity is 84-86%.

Chemical shift imaging is less sensitive than washout CT for detecting lipid-poor adenomas, in particular when unenhanced CT density is 20 HU or higher [13].

This adrenal lesion was discovered on a pulmonary embolism scan.

Using the Adrenal MRI calculator the adrenal spleen ratio (ASR) and signal intensity index (SI-index) can be measured from ROIs placed inside the adrenal lesion and the spleen on both the in-phase and out-of-phase images.

Based on the signal intensities measured within ROIs placed over the adrenal lesion and spleen the ASR is 0,66 ( < 0,71) and and the SII is 39,5% (>16,5%), indicating that this is an adenoma.

Malignant tumors have higher glucose metabolism than benign tumors.

This enables PET-CT imaging with the glucose analogue 18F-fluoro-deoxy-glucose (FDG).

FDG is not specific for any certain adrenal tumor, but can be used to differentiate pheochromocytomas, paragangliomas, adrenocortical carcinomas and adrenal metastases from benign tumors.

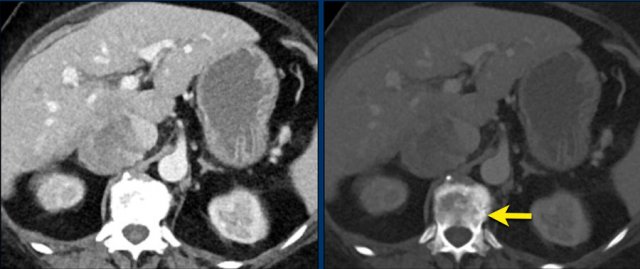

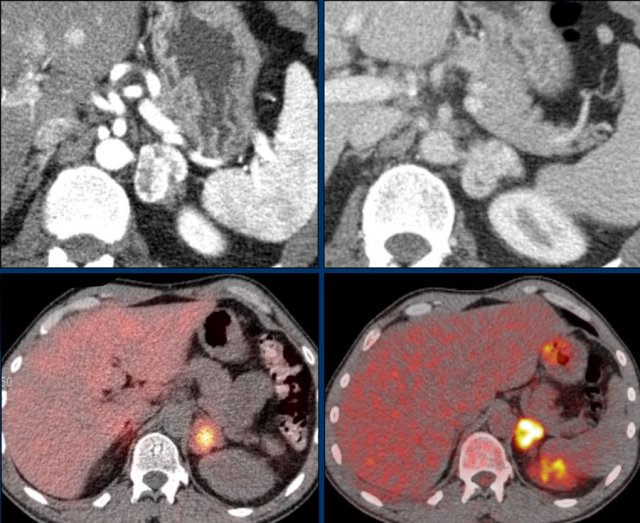

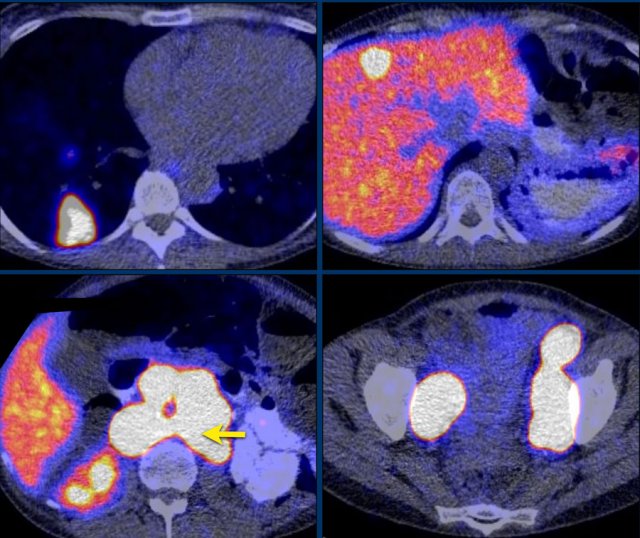

Axial venous phase CT in mediastinal and bone window setting

Images depict mediastinal and bone window setting of a patient with a bulky heterogeneously enhancing right adrenal tumor.

This was proven to be an adrenocortical carcinoma.

There is a faint, ill-defined liver lesion in segment 6 and there are non-specific sclerotic changes in the body of T12.

Continue with the PET-image.

PET-CT performed for complete staging shows intense uptake in the adrenal tumor, indicative of its malignant nature.

There is also intense uptake in two liver metastases and in a bone metastasis in T12.

Approximately 20-40% of patients with an adrenocortical carcinoma present with metastases at diagnosis.

Whole-body FDG PET-CT can distinguish benign from malignant lesions with high sensitivity (100%), but with lower specificity (87- 97%).

False positives are due to a small number of adenomas, pheochromocytomas, inflammatory and infectious lesions, that mimic malignant lesions [14].

Possible false negatives are hemorrhagic, necrotic or small (5-10 mm) metastases and metastases from relatively low FDG-avid primary cancers, like minimally invasive adenocarcinoma or carcinoid tumors [14].

Apart from visual evaluation it is also possible to use standardized uptake values (SUVs) with a certain cut-off value (SUVmax 2,68-3.7) or an adrenal-to-liver SUV ratio (reported cutoff values 1.29-1.45) to differentiate benign from malignant adrenal lesions, with high sensitivity and specificity [14, 15].

Combining FDG PET-CT and adrenal washout CT can further improve the accuracy for diagnosing adrenal malignancy [16].

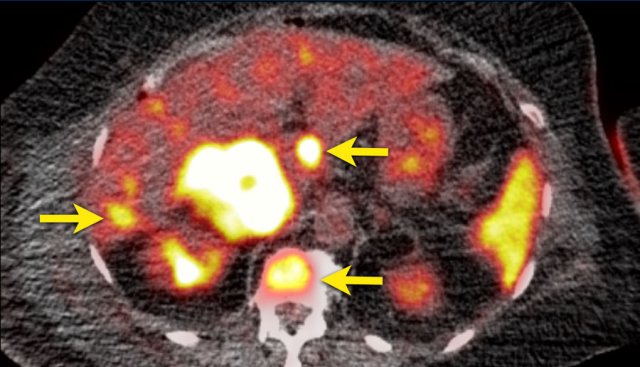

This axial venous CT shows a very bulky right adrenal mass, suspicious for a malignancy, based on the large size and heterogeneity.

This lesion is an adrenocortical carcinoma, but in contrast to the former example, subsequent FDG PET-CT performed for staging purposes showed only mild uptake and only in the most avidly enhancing part of the tumor.

Most adrenocortical carcinomas show intense FDG-uptake.

This lack of FDG-avidity might be due to a lower grade tumor with lower mitotic rate or large hemorrhagic or necrotic components.

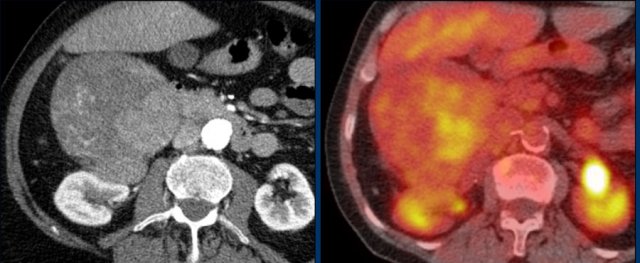

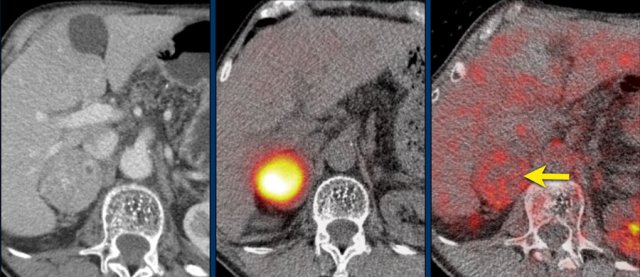

First postoperative axial venous phase CT performed 3 months after left adrenalectomy for a large adrenocortical carcinoma showing an enhancing nodule posterior to the left kidney.

Restaging FDG PET-CT showed intense uptake in only this lesion, which proved to be a metastasis on subsequent follow-up imaging.

The left renal subcapsular hematoma is unrelated.

Axial arterial and venous phase CT show a hypervascular left-sided adrenal incidentaloma.

Plasma free metanephrines were elevated, diagnostic of a pheochromocytoma.

Further staging included a MIBG SPECT and a FDG PET-CT, which both showed intense uptake in the left adrenal tumor, but no evidence of metastatic disease.

Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas originate from chromaffin cells in the adrenal medulla.

These are neuroendocrine cells that express cell membrane norepinephrine transporters and secrete catecholamines, noradrenaline, dopamine and a few other hormones.

This is the basis for the use of tracers like 131I- and 123I-MIBG, which accumulate within adrenergic tissue, making MIBG scanning specific for pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas.

18F-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) and 18F-fluorodopamine (DA) are 18F-labeled pheochromocytoma-specific compounds which can be used for PET-CT imaging [19].

Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas also have somatostatin receptors and thus can be imaged using somatostatin analogues.

The somatostatin scan (or Octreoscan) is now being replaced more and more by PET-CT using 68 gallium-labeled somatostatin analogues like DOTA-TOC, DOTA-NOC or DOTA-TATE [19].

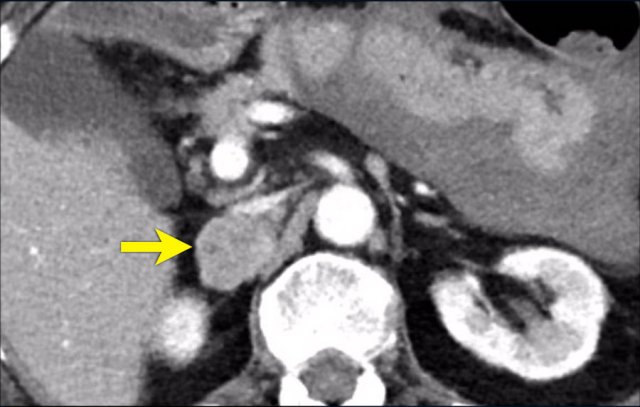

The axial venous phase CT on the left shows a large inhomogeneously enhancing right adrenal lesion with a small cyst, which could not be diagnosed as an adenoma with CT washout, making it an indeterminate lesion.

The plasma free metanephrines were elevated and the lesion was diagnosed as a pheochromocytoma.

MIBG SPECT for staging showed intense uptake in only the right adrenal gland.

PET-CT was also performed, which in contrast showed uptake only slightly higher than normal liver.

This is highly unusual for pheochromocytomas, which are usually very FDG-avid, even when they are benign.

If the primary tumor lacks FDG uptake, the sensitivity for finding metastases on an FDG PET-CT will be very low.

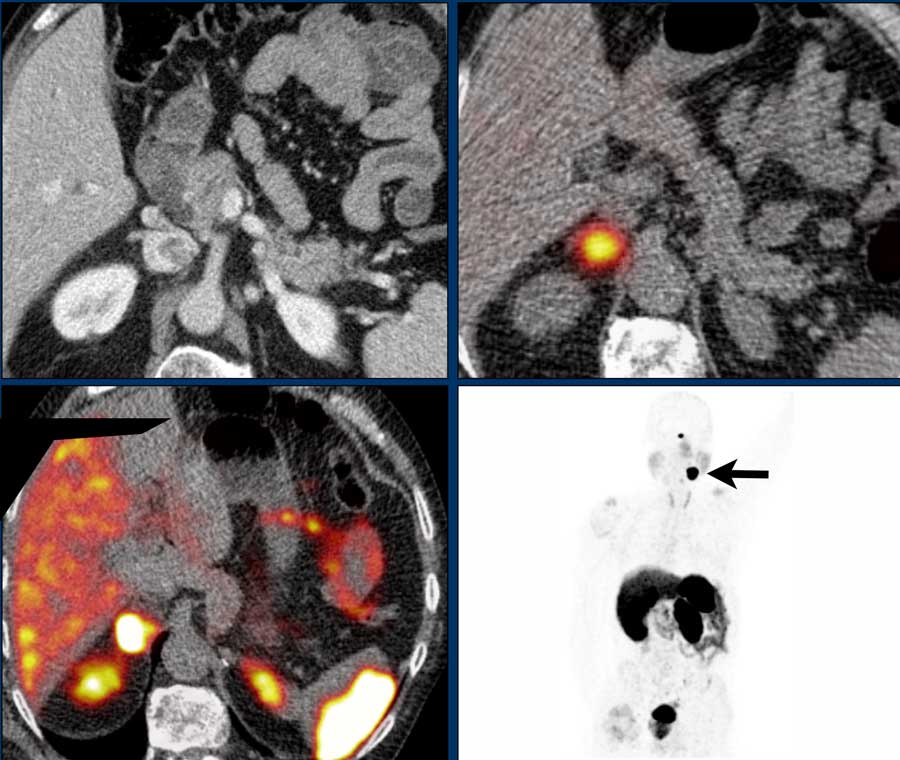

The upper left image is a venous phase screening CT in a patient with a known SDHD-gene mutation which is associated with a high risk for developing pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas.

There is a hypervascular right adrenal tumor.

A MIBG SPECT was performed, which showed intense uptake, helping to confirm the diagnosis of a pheochromocytoma.

A year later, screening was performed with 68 Ga- DOTATATE PET-CT.

This shows intense uptake in the right adrenal gland, but also intense uptake in a glomus caroticum tumor on the left as seen on the coronal MIP to the right.

The DOTATATE uptake in the spleen and pituitary gland are normal, as is the normal excretion by the kidneys to the bladder.

Pheochromocytomas express somatostatin receptors, making them suitable for imaging with a somatostatin-analogue.

In this case 68 gallium-labeled DOTATOC is used.

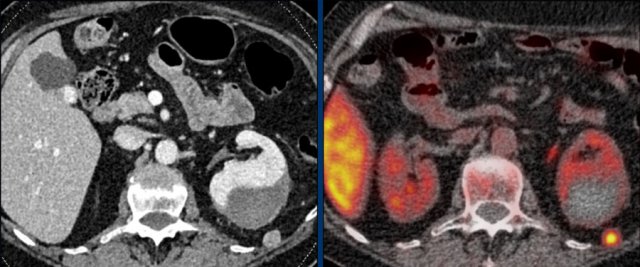

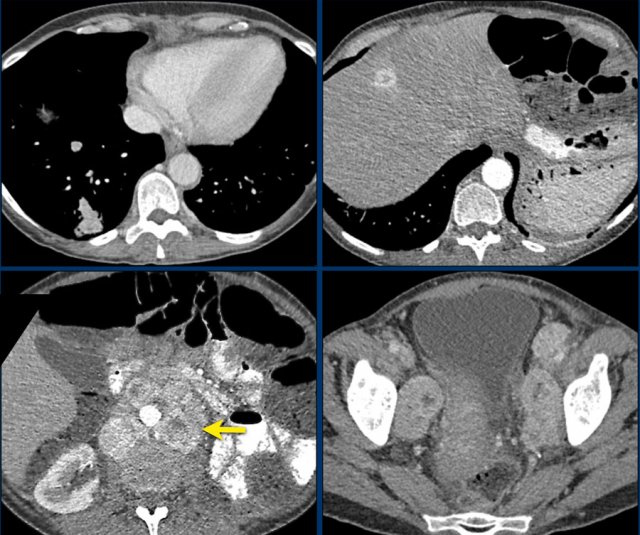

This patient presented with widespread metastatic disease to the lungs, liver and retroperitoneal lymph nodes after resection of a pheochromocytoma.

Continue with the PET-CT.

PET-CT of the same patient with 68 gallium-labeled DOTATOC.

Up to 15% of all adrenal tumors are functional:

Current guidelines from the European Society of Endocrinology (ESE), American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and the American College of Radiology (ACR) [2,3] recommend an initial biochemical evaluation of all adrenal incidentalomas to exclude pheochromocytoma, subclinical Cushing's syndrome and hyperaldosteronism.

The following hormones should be assessed in all patients with an adrenal incidentaloma:

The following hormones should be assessed conditionally :