When the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) took control of China in 1949, the national economy was underdeveloped and lacking in heavy industry, mining, steel production, manufacturing and infrastructure. China’s 1953 census revealed an increasing birth rate and a population approaching 600 million. This population growth only emphasised the need for increased production and economic growth. Following the Korean War, Mao Zedong and the CCP decided to prioritise economic development. Drawing on his experiences during a 1949 trip to Moscow, Mao embraced the Soviet ‘five year plan’ model for economic development. Mao had previously concentrated his energy on the peasants – but his end plan became the transformation of China into a modern industrial power. Historian Michael Lynch believes that Mao’s economic goals were used to sideline potential political rivals: “Mao exploited the atmosphere, in which anything short of total acceptance of the plan was deemed counter-revolutionary”. In 1953 the People’s Daily echoed the Chairman, telling its readers that “only with industrialisation of the state may we guarantee our economic independence and non-reliance on imperialism”.

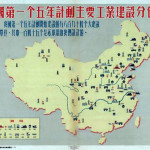

China’s First Five Year Plan was an economic program that ran from 1953 to 1957. It set ambitious goals for industries and areas of production deemed priorities by the CCP. The Five Year Plan was supported by Soviet Russia, which contributed advice, logistics and material support. Moscow provided a small loan of $300 million and, more importantly, the services of several thousand Soviet engineers, scientists, technicians and planners. On paper, the achievements were impressive. Industrial output more than doubled, with an annual growth rate of 16 per cent. Steel production grew from 1.3 million tonnes in 1952 to 5.2 million tonnes in 1957; the 16.56 million tonnes produced in 1953-57 was double China’s combined steel production between 1900 and 1948. Overall the largest increases in output were in steel, coal and petrochemicals, with coal production increasing 98 per cent between 1952 and 1957. While the First Five Year Plan achieved its targets of increasing heavy industry and stimulating the economy, these advances worsened the imbalance between rural and urban populations, with serious implications for the new society. Like the economic reforms in Soviet Russia, China’s emphasis on industrial growth came at the expense of agriculture. Grain output struggled to keep pace with population growth, jeopardising food supplies.

A good deal of China’s economic growth in the mid-1950s centred on urban, industrial and infrastructure projects. These works enhanced the quality of life for urban populations, whose numbers increased from 57 million to 100 million between 1949 and 1957. Life expectancy rose from 36 to 57 years, city housing standards improved and urban incomes increased by 40 per cent. Workplaces were organised on socialist principles; urban and industrial workers subsidised housing, medical care and educational facilities. Mao saw the political benefits of such improvements, saying in 1957 that “If China becomes prosperous, just like the standard of living in the Western world then [people] will not want revolution”. Yet despite these improvements, the state continued to expand its influence over citizens. Life for urban Chinese was tightly regimented by way of danwei or work units. The danwei provided the basic structure for labour and controlled many aspects of everyday life, including accommodation, education and social services. People even had to consult their danwei in matters regarding to marriage, having children or travel.

These economic reforms also increased centralised state control, to the extent that private ownership became virtually impossible. By 1956, approximately two-thirds of industrial enterprises were state-owned; the remainder were jointly owned. Rigid central planning and national demands often resulted in local needs being neglected, especially in the countryside. While 84 per cent of the population lived in rural areas, 88 per cent of government investment was pumped into heavy industry in towns and cities. The state monopoly on grain and the impact of collectivisation also caused disruption and dissatisfaction in rural areas in the mid-1950s. Many questioned whether the struggling countryside could feed the rapidly expanding cities. As the state diverted grain supply, grain reserves fell, causing food shortages and hunger in some places. New farming techniques and technologies, used with success elsewhere in Asia, were largely ignored.

“The First Five Year Plan produced results that were impressive enough to sustain the Chinese leaders’ dreams… Of course, agriculture could not grow at anything like this pace. Though agricultural production and rural economic conditions were not in deep crisis, their level of performance was a thin reed upon which to rest grandiose plans for rapid industrialisation.”

Marc Blecher, historian

The process of agricultural collectivisation began to gather pace in 1955 and 1956. High production targets were introduced, food distribution disrupted and the government took ownership of all land and equipment previously redistributed. Hostility to the process even led to physical attacks on officials. Meanwhile, tens of millions left the countryside for the more comfortable cities, placing further strain on collectives to feed bulging urban populations. By the end of the First Five Year Plan about 93.5 per cent of farm households had been collectivised – an outcome, according to Mao Zedong, that would solve the problems of the rural world. While government rhetoric and propaganda heralded the First Five Year Plan as a success, the burdens felt in the countryside quickly approached breaking point. Mao’s ambitious plans for further industrial growth would soon give rise to the looming disaster known as the Great Leap Forward.

1. The First Five Year Plan ran from 1953 to 1957. It was based on a Soviet model for economic and industrial expansion and marked a shift in focus away from the peasants toward urban industrial projects.

2. The greatest increases were in steel and coal, with steel production beating expected targets. Steel production grew from 1.3 million tones in 1952 to 5.2 million tonnes in 1957.

3. The First Five Year Plan significantly shaped life in industrial urban centres. Quality of life improved, indicated by significant increases in life expectancy, housing and income – however, everyday life was also strictly controlled through the danwei, or work unit.

4. State ownership dramatically expanded during this period so that most enterprises, food distribution and land all came under centralised government control. This had adverse effects on rural areas, with grain production not keeping pace with industrial and population growth.

5. The first cracks appeared towards the end of the First Five Year Plan, as the increasing demand to feed an expanding urban population intensified criticism and opposition to rural collectivisation.